2020-09-14

A career in music?

Once in a while, a young person will say, "I might want to have a career in music." This statement makes me think of a hundred things all at once; the only real response I can ever give to it is "OK, let's talk about what that means."

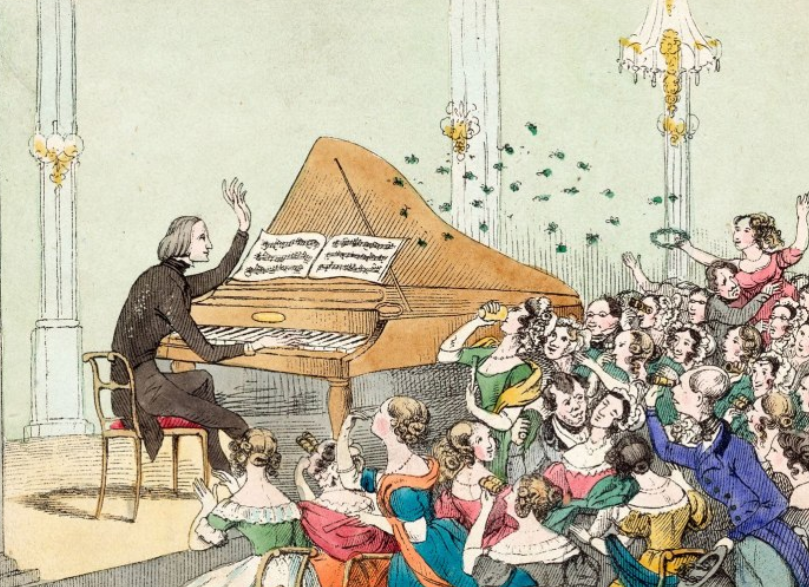

When I was a teenager, there was still the prospect that a highly skilled concert pianist might actually be able to spend the majority of their time in a career playing the 17th to 20th century European repertory they knew and entertaining audiences who loved that repertory. Those audiences would also buy concert tickets and recordings to an extent where the musician might actually be able to focus entirely on playing. That would constitute a "career", a very 19th century model of music making that by 1975 was already being eroded heavily by several forces: the incredible social and financial pull of popular music and the rapid development of new technologies to distribute music and connect music lovers.

Now, about 50 years later, the market for Western concert music has changed beyond recognition. Yes, thank goodness, it is still with us... but... it survives in an incredibly noisy world of hundreds of musical genres, all available at any moment of the day (or night) through our devices. This sheer immediacy and ease of access has virtually destroyed the idea that performers "own" their performances; milliseconds after a digital work is released, it is in the hands of potentially millions of listeners, via means that overwhelmingly bypass compensating the artists for their efforts. In our world today, if you have access, you own it. It is that simple. Good luck trying to get paid for it.

So where do musicians fit in all this? It is difficult to say. Most concert artists, and for that matter, rock bands, will tell you that they basically give away live performances to drive potential customers to their digital sources. But even then, there is no guarantee of return on your investment. For many musicians, it often feels like the last remaining reason to pursue the art is for one's own love of it; and that, surely, will not provide something you can live on, at least not in North America today.

Musicians, therefore, most often become musical polyglots. Almost all the "professional" musicians I know today devote part of their weeks to at least one branch of the discipline (teaching, often) or a completely different career to survive. The tragedy in this is that one really needs to spend >all< one's working hours on music performance (or any single aspect of music) if you want to master it.

There is so much more to say about each one of these points; perhaps they should be stepping off places for a series of articles. I will say, however, that a surprising amount of Western music appears headed back to a model that was common 300 or more years ago: the musician as amateur. Humans have always incorporated music in life; researchers continue to find the extraordinarily deep and visceral rôle music plays in the psyche. We literally cannot live without it. It therefore is no mystery that people constantly find ways to make music in their leisure time: rock, blues, jazz, ethnic, Gospel, "Classical". This is, indeed, the advice I have given to more than one student over the years: make music an integral part of your life and make your skills as strong as possible. That way, you can play music in your leisure time on your own and with others. It will give your life meaning and richness all the way through.

What to do with the prodigies? That is, indeed, a topic for another day. But let's conclude today by saying that genuine prodigies are extremely few and far between and that they are the rare exceptions to the prevailing rule at this point in human history.

If you have more questions about this topic, don't hesitate to contact me and we can chat.

K

Previous blog entries